by Camille Bacsa

How much do you really know coffee? Aside from being your go-to elixir when the going gets tough and you have to keep your eyes open, what really makes it special? And while you might be most familiar with the big foreign coffee brands out there, did you know there are hidden treasures right within Philippine soil? In fact, the Philippines is one of the very few countries in the world that can produce the four most in-demand types of coffee beans: Arabica, Robusta, Excelsa, and Liberica. Here at the BiteSized HQ, we got curious and decided to dig deeper and get the low-down with Philippine Coffee Board Inc.’s (PCBI) Ms. Pacita “Chit” Juan – after all there is more to your kapeng mainit than meets the eye, owing to its rollercoaster journey from foreign soil to Pinoy mugs.

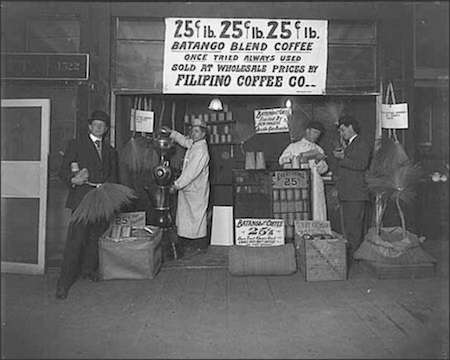

Similar to Catholicism, coffee reached Philippine shores through the Spaniards. In particular, the first coffee tree brought by a Spanish Franciscan Monk was planted in 1740 in Lipa, Batangas, where the volcanic soil, low temperature, and cultivation practices allowed it to flourish, thereafter expanding to nearby cities like Ibaan, Lemery, San Jose, Taal, and Tanaua – establishing Batangas on the map as the coffee capital of the Philippines. By the 1860s, Batangas is already exporting coffee to the US through San Francisco, later conquering Europe upon opening of the Suez Canal. This uphill ride continued until the 1880s with Cavite joining the bandwagon, positioning the Philippines as the 4th largest exporter of coffee beans.

In 1889 though, the same coffee rust that plagued Brazil, Africa, and Java eventually hit Batangas, and paired with an insect infestation, these practically wiped out coffee harvests down to just 1/6th of its original quantity in a span of two years. The industry dwindled as farmers switched to other more productive crops, and Brazil regained its global market leader status in coffee harvests.

With advancements in farming technology though, the Philippines was back in the spotlight when the US introduced more resistant species of coffee beans in the country, just in time for the growing demand for instant coffee mixes by the 1960s.

According to Juan, the coffee industry “peaked in the 70s and then declined in the late 80s” as the market became saturated. The decline in the 1980s was due to the surge of supply, causing governments to impose importation bans and making coffee trade the most cut-throat it has ever been. Regardless, all four types of coffee were still produced in the 276,000+ coffee farms all over the Philippines by the 2000s – with Robusta claiming the majority of production at 75%. Most coffee farms span 1 to 2 hectares. “Philippine coffee is generally still grown in smaller farms and are almost always organic by default,” Juan said.

The challenging, volatile ride doesn’t end there. Since it takes 3 to 5 years to grow coffee crops and the yield per hectare is relatively low, many farmers choose to shift to other higher-yielding crops like corn or rubber. Filipinos who continue to produce coffee though remain marketable for the top-tier quality of their product – which is venerated by the growing number of coffee enthusiasts in the country and around the world – giving them a fighting chance against Vietnam, from whom we heavily import higher-yielding Robusta coffee. This burgeoning interest for artisanal coffee is breathing in new life to the industry, and likewise, we Filipinos ought to understand exactly what makes our coffee special and a sought-after delicacy, despite being pitted against competitively priced coffee from other parts of the world.

We’ve been talking about four types of coffee beans for a while now, but how do they really differ and where do we find them? For starters, your budget-friendly 3-in-1 is typically made with roasted Robusta or Arabica beans, with robusta taking the cake for almost double the caffeine content, but Arabica being more flavorful and typically more expensive. Seasoned coffee aficionados will describe that Arabica coffee is sweet in taste and floral in aroma with some of the best beans hailing from the Cordilleras, whilst Robusta is sharp with a heavy body and woody aftertaste, widely grown in Cavite, Bulacan, and Mindoro. Liberica has a bittersweet, dark chocolatey flavor with fruity and smoky notes, with the Kapeng Barako of Batangas being one of its rarest and classified into a category by itself for its distinct aroma and bold flavor. Excelsa, while somewhat similar in taste to Robusta and Liberica, stands out when in its purest form because it has a sweet, langka-like flavor and typically cultivated today in Batangas, Quezon, Sorsogon, and Bicol. All four types can be roasted to varying degrees to discover a spectrum of flavors that will satisfy different tastebuds. While the way coffee is harvested and processed also have significant effects on its taste, the general rule is that the darker the roast, the lesser the caffeine, acidity, dryness, and origin flavor of the coffee beans.

With this understanding, more and more Filipinos are becoming discerning of their brews, giving birth to the third and fourth waves of coffee in the Philippines. “Philippine coffees are now sold in smaller lots that command higher prices due to its quality. There is a demand from local roasters,” Juan shared. Just a quick stroll around the city and you’ll notice that the players aren’t just the big international coffee chains anymore. Artisanal cafés serving specialty coffee are sprouting left and right, with baristas confidently sharing their coffee knowledge to inquisitive customers. Even coffee competitions are increasing in popularity and frequency, with the 5th Philippine National Barista Championship, 4th Philippine National Latte Art Championship, 1st Philippine Brewers’ Cup, and 1st Philippine Coffee in Good Spirits all happening in March 2018 (read more about these at Philippine Coffee Championships).

Juan also shared that Filipinos consume about 120,000 metric tons of coffee annually, but is only able to produce 35,000 metric tons – the difference mostly being imported as instant coffee. To match consumer demand and the shift towards artisanal coffee, movers and shakers in the industry must find ways to resolve the primary challenges in local coffee production, namely: the threat of imports, low yields, and a long wait before a return on investment. “There are talks to create a coffee group to probably provide funds for seeds, planting materials, and fertilizers. But because it’s cheaper to import from Vietnam, we may not be able to compete with their productivity. The way to address the imports is to make most of our coffee specialty coffee, not just instant or soluble,” Juan imparted.

A campaign has also been launched to teach farmers to only pick the fruits when ripe, which was once a bad practice especially in the provinces. More importantly, PCBI is working hard to position the Philippines as a producer of high-quality specialty coffee that is at par with the world’s best to command better prices even with smaller volumes in the global market. Farmers do not need to just roast coffee for better prices as they can also get better value even for green or unroasted coffee. By training Quality Graders to taste test our produce against The Coffee Quality Institute’s standards, Filipino farmers can make a bigger name for themselves in the global coffee industry.

Needless to say, coffee has had a long up-and-down journey in our country, and its future will likely be just as colorful. “Drink local coffee to further spur farmers to plant more. Choose you coffee and know where it’s from. Asking for its origin forces the cafe owner or the retailer to know the farmer, so farmers can sell directly to the roasters and cafe owners,” Juan advised.

With our love and addiction for this warm, comforting, and caffeinated elixir to get through our long and tiring days – there is no doubt Filipinos will find ways to make this treasured industry blossom in the years to come. As a head start, keep sipping and drink local!

Leave a Reply